|

|

How important is religion to people in Europe? In Muslim nations, about ninety percent declare that religion “plays a very important role” in their lives, while the United States figure in 2002 was about sixty percent. The average figure in 2002 for Europeans was twenty-one percent, with national variations (Italy, twenty-seven percent; Germany, twenty-one percent; France, eleven percent). A survey of British respondents in 2004 found only forty-four percent professed a belief in God; thirty-five percent did not believe in God.

The Dramatic Decline of Churchgoers in Europe

European levels of church attendance are deteriorating. Forty percent of Americans visit a place of worship weekly, compared with less than twenty percent in most of Europe. The British attendance figure is fifteen percent, with twelve percent in Germany and less than five percent in Scandinavia—and these figures include attendance at any place of worship, whether church, mosque or synagogue. Between forty and fifty percent in Scandinavia practically never attend a place of worship.

The Evangelical Church in Germany, EKD, which includes most Protestants, has lost over half its membership in the past fifty years. Only one million of its twenty-eight million members demonstrate any regular participation.

What are the reasons for this drastic decline? There are a number of reasons, including the effects of the Enlightenment, secularisation and the consumer society. My thesis in this article is, however, that the Constantinian structures of churches in Europe, and particularly in Protestant northern Europe, have played a significant role. I am well aware that formal state churches are rare today and found only in Norway and Finland (and for all practical purposes in Denmark); however, the state church structures have actually, since Constantine in AD 313-325, played an essential role in most of Christendom. ![]()

Gospel Reductionism

Darrell L. Guder wrote in 2000 about the conversion of the Church. This conversion is related to re-thinking theology, evangelization, worship, leadership and structures. Most importantly, it demands undertaking measures against the gospel reductionism within the Church. The early Church went from “movement” to becoming an “institution.” Constantine’s Church replaced the understanding of the gospel with a focus on an event with the formulation of a defined faith system consisting of truths. The Kingdom of God was conceived as the eternity that awaits a Christian after death; salvation was given to the individual by the church, in particular through the sacraments. On the basis of these gospel reductions, the organizational structure of the Church was transformed into state religion and the administrator of religious meaning in society.1 Likewise, according to Guder, the reformation and pietism have reduced the gospel to a matter of salvation for the individual:

“The benefits of salvation are separated from the reason for which we receive God’s grace in Christ: to empower us as God’s people to become Christ’s witnesses. This fundamental dichotomy between the benefits of the gospel and the mission of the gospel constitutes the most profound reductionism of the gospel.”2

Structures and Secularisation

These structures have, in the course of the centuries and in close collaboration with the Enlightenment, also paved the way for the so-called secularisation (“so-called” because most scholars were wrong when they predicted that religion would lose its influence and eventually disappear). What actually occurred was that Christianity and the Church lost its support and position within Western society and have become increasingly marginalized, while at the same time religion in general has flourished throughout the rest of the world. In England, church membership has fallen to fifteen percent, and in several East-German cities memberships have dropped as low as ten percent. In my time, church membership in Denmark has dropped by fifteen percent, and church attendance has decreased by seventy-five percent.

At the same time, our Scandinavian societies have developed into multi-societies (multiethnic, multicultural and multi-religious). In the midst of this development, faith is cut loose: one-third of the Danish population believes in reincarnation, and large groups make use of religious or quasi-religious therapists.3

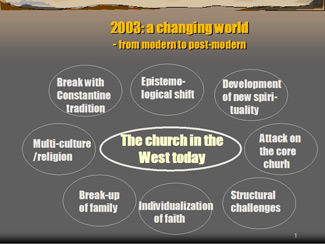

A 2003 overview sketches some main challenges to churches from the Constantinian era:

|

The Need for New Paradigms

In his pioneer book on missiology4, South African missiologist David Bosch claims that we are experiencing a shift from the modern Enlightenment paradigm in the history of Christendom toward a postmodern, ecumenical paradigm. In this shift, old answers will not suffice. A paradigm shift requires a shift in worldview. Above we have looked at the dramatic changes in the established churches of the West which led to the closure of the era of Christendom. During the last decades of the twentieth century we experienced a religious shift from the North to the South, and a shift of gravity with regard to church and Christians: a massive growth in the South and East, whereas Western churches experienced a disastrous decline. ![]()

Thus it is clear that Corpus Christianum—the idea of a unity made up of state, religion and culture as the canopy for the Church’s work—no longer functions. The West is witnessing the end of an era that lasted from the Constantinian state Church and Church tradition dating from the fourth century. This calls for a dramatic readjustment process. The idea of Corpus Christianum symbolized wedlock between the Church and the holders of power, which, in different ways, turned a missionary Church into a pastoral institution.

As the state religion of Rome, the Christian faith became the civil religion and the society’s administrator of religious meaning. The Church’s structure adopted the shape of society’s structure, with parochial churches, and a clear division between clerici (priests) and idiotes (lay people). Faith was practiced by taking part in the arrangements of the Church, and evangelization was replaced with (forced) “Christianization.” Breaking with the Constantinian tradition and its access to power and influence is not easy. In other parts of the world, a break with the Constantinian Church has already taken place, or it has never been present in the first place. To us in Europe it has become an obstacle to mission because it conceals the fact that we are situated in a mission context.

According to Stanley Hauerwas, “Constantinianism is a hard habit to break. It is particularly hard when it seems that we do so much good by remaining in ‘power.’ It is hard to break because all our categories have been set by the Church’s establishment as a necessary part of Western civilization.”5

Most often I meet the following argument: The Constantinian structures, with parishes, pastors and public support, offer a multitude of opportunities for relating to people in connection with baptism, confirmation, wedding and funeral. In the Christendom era when the population was largely Christian, the argument was valid; however, it is not valid in a situation where we actually find ourselves in a mission situation.

In such a mission situation, “Christianization” is no longer the answer. A mission situation calls for mission, because our European societies are no longer homogeneous culturally and religiously. We are confronted with a multicultural and multireligious context where the state church structures are obsolete. And we are confronted by a postmodern culture where the parish structure no longer attracts people in the cities and only partially in the countryside.

Missional Church

The alternative for many in Europe is a missional Church. The vision to be a missional Church is born out of a critique of our conception of being church. The response to a mission situation is not to initiate efforts to “communicate with modern humanity”; rather, it is to ask what is wrong with today’s Church since the gospel appears so irrelevant to so many. ![]()

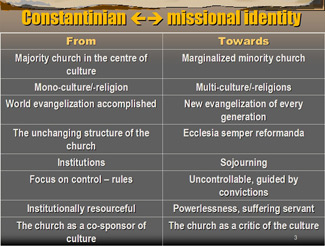

The features of the Constantinian Church are similar to a Lutheran conception of the Church as the place for preaching of the gospel and administering the sacraments. A missional Church is where the people of God—in following Christ—participate in God’s mission through being, word and deed in their daily lives. The symbols of the Constantinian Church are the place, the temple, the word, the sacred; whereas, the symbols of the missional Church are the way, discipleship, wholeness and everyday life. Likewise, one can distinguish between the custodians of the Constantinian Church—a clerical hierarchy of static institutions—and the custodians of the missional Church—lay people who dynamically live out their faith in everyday situations.

|

In the midst of this paradigm shift, the question is: How can we be God’s Church in our time? This is not a matter of new methods or models. Encountering the challenges of the Church and a changing society, Europeans tend to think in terms of analyses, solutions and projects—new church models, electronic church, reshaped worship and evangelization efforts.

In reality, the shift we experience raises questions about the theology and spirituality. We are forced to reread scripture about what it means to be God’s people in the world. In this light, one can only wonder how, for decades, we have made the whole known church structure such an integral part of the gospel, and how we have carried out a determined reduction of the gospel (from making disciples to a preoccupation with the personal salvation of the individual) and what it means to be Church—from the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church to a Church that defines itself only by what it does (i.e., the preaching of the gospel and the administration of baptism and communion). In this way, the reformers shifted the attention away from what the Church is to what the Church does. Through this focus on sermon and sacraments the church service became the primary task of the Church. The reality is, the Church is also called to engage in functions like fellowship, making disciples, service and witness. Wilbert Shenk is preoccupied with the same issue:

“The confessional statements…all emphasize the function rather than the being of the Church. Ecclesiologically, the Church is turned inward. The thrust of these statements, which were the very basis for catechising and guiding the faithful, rather than equipping and mobilizing the Church to engage the world, was to guard and preserve.”6

In this way, there was little room for the gifts of the Spirit, equipping, mission and the service of lay people. ![]()

The term missional Church is an expression of the fact that the Church is not primarily the institution with services, activities and a mission in the periphery. Therefore, the task is not to invent a number of mission programs aiming to attract new churchgoers. Instead, we are challenged to be people of flesh and blood carrying the reality of the gospel within themselves, communicating it through missional being and action. For that reason, it is likely that the famous, but seldom realized, priesthood of all believers will become the basic Church and mission structure. Together with this structure, one could hope for a rediscovering of the gifts of the Spirit in a broad biblical conception.

This focus on church as mission also means that our ability to be magnets attracting people to Christ becomes important. Therefore, a missional Church should emphasize meditation, spirituality, presence, genuineness and lifestyle. Modelled by our brothers and sisters in the South and East, we should become personal carriers of the spiritual reality the world longs for. Before becoming centrifugal we should return to the centre.

And when going out, our primary task is to be witnesses. The missional thinking often and markedly underlines that the Church’s missional call is to be witnesses. Mission is witness. Martyria is the sum of kerygma, koinonia and diaconia—all of which constitute important dimensions of the witness by which the Church is called and sent with. According to Guder, “We are using a missiological hermeneutic when we read the New Testament as the testimony (witness) of witnesses, equipping other witnesses for the common mission of the Church.”7

Thus, testimony becomes a demonstration through the lives and actions of God’s people to the fact that the Kingdom of God becomes present in the disciples of Jesus Christ. This is how the testimony of the gospel defines the identity, activities and communication that the Church has been called to since Pentecost.

Rather than Constantinian structures, we need to mirror the following:

- Humility. A recognition of weakness and crisis

- Variety. Various ways to be church (i.e., family, synagogue and temple)

- Lay-person focused. Focus on lay people as the ordinary pastors, and the ordained pastors as assistants to the ordinary pastors

- Contextualization. A more profound engagement with both culture/context and the Bible

- Defining mission. A reinterpretation of mission as what the Church is, does and says, including: development of spirituality, involvement in the culture of the local community, learning to speak of our faith and learning to listen and to encourage dialogue with people outside the Church.

Endnotes

1. Guder, Darrell. 2000. The Continuing Conversion of the Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA: Eerdmans. 103ff.

2. Ibid. 120.

3. See also Leif Gunnar Engedal and Arne Tord Sveinall’s analysis of Norwegian conditions in Troen er løs. 2002. Oslo: Egede Instituttet.

4. Bosch, David. 1991. Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. Maryknoll, New York, USA: Orbis Books.

5. Hauerwas, Stanley. 1991. After Christendom? How the Church Is to Behave if Freedom, Justice, and a Christian Nation Are Bad Ideas. Nashville, Tennessee, USA: Abingdon. 18.

6. Shenk, Wilbert R. 1995. Write the Vision: The Church Renewed. Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, USA: Trinity Press International. 38.

7. Guder. 2000. 53-55.