Although churches can grow in numbers whether they have a pastor or not, a greater proportion of churches report growth when they have a pastor (sixty-eight percent) than when they do not (thirty-seven percent). This is one result of a detailed 2003 report from the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches (FIEC, a UK denomination). Still, churches without a pastor were more likely to have remained stable (thirty percent) than those with a pastor (twenty percent). This relationship between leadership and growth is neither new nor confined to the FIEC. Other studies have shown such a link. Why is leadership important in this context? Leaders often provide vision, and it is this sense of dynamic and purpose which is attractive to new people joining congregations.

Number of Ministers

In 2005 there were 34,400 ministers for the UK’s 47,600 churches—1.4 churches for every minister. Some denominations (Anglicans and Methodists especially) share ministers across several churches; one study found that up to four churches could often be reasonably handled by one minister, but more than that was often beyond a single individual’s ability to cope. Other denominations, especially Pentecostal, look to part-time ministry rather than full-time leadership. As a consequence several ministers may be needed for an individual church, one person being appointed as responsible for preaching (not necessarily doing it all by him or herself), another as responsible for pastoral work, another for prayer, another for prophecy and so on. The concept of team ministry is likewise increasingly popular, with one person in a senior leadership role.

Gender and Age of Ministers

The proportion of female ministers in the UK was seven percent in 1992; by 2005 that number was up to twelve percent. Some denominations, like the Roman Catholics and the Orthodox, have no female ministers, while others, like the Salvation Army, have over fifty percent. In 2000 twenty-two percent of ministers in the United Reformed Church were women, nineteen percent of Methodist ministers were women, fifteen percent of ministers in the Church of Scotland were women and twelve percent in the Church of England were women. And these percentages are slowly increasing.

The average age of a minister across all denominations in 2003 was 53, slightly less than the average age of 55 for churchgoing adults. Roman Catholic priests were the oldest and those leading new churches were the youngest (58 and 48 respectively).

Duration of Ministry

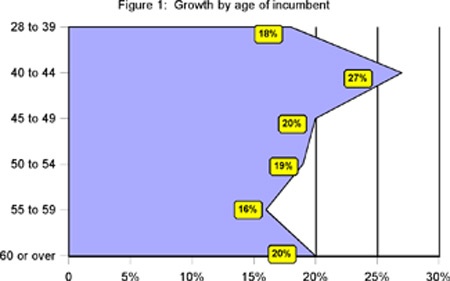

According to a 2003 survey, ministers had been in their present post an average of ten years. Those in Independent churches stayed the longest (fifteen years) and those in Methodist churches the shortest (seven years). In a detailed survey of Anglican ministers, both age and length of ministry were important for church growth. This was more likely to occur when a minister had been in a post for seven to nine years, and, as Figure 1 shows, when he or she was either in their early 40s or in their 60s.

|

Future Trends of Ministers

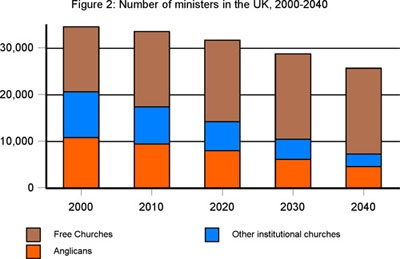

How will the number of ministers most likely change in the next few decades? There are a number of different elements to be taken into consideration. Figure 2 shows that the overall trend is downwards, so that by 2040 there could be only twenty-six thousand ministers in the UK.

The possible decline in number is especially seen in the “other institutional churches” which reflects the decreasing proportions of Roman Catholic priests. Fewer men are entering the priesthood, and those already serving average the oldest of all ministers and will have to retire within the next twenty years or so, even if Catholic priests serve until they are 75 or 80. Anglican numbers are declining also, but will be compensated by an increased number of non-ordained or locally-ordained “readers” or ministers appointed to serve in specific congregations. ![]()

Figure 2 shows an increase in the number of Free Church ministers. This increase is entirely within the Pentecostal group where more part-time ministers will be needed to serve the likely continuing increase in numbers of black and other ethnically diverse churches. These churches are currently growing both in number and size and this is expected to remain the case for at least another twenty years.

|

While the number of church members, church attendees and churches are also set to decrease within the next three decades, the rate of decline in the number of ministers is the smallest of all. Their leadership therefore becomes more important, and the way it is exercised becomes increasingly significant for the future of the Church.

The calibre of that leadership, and its vision for the future becomes critical for the well-being of the Church over the next three decades. Some of the key issues to be considered therefore are:

- How are these men and women selected?

- How are conditions of service presented to attract new ministers?

- What are the key giftings ministers will need for their churches?

- How do they obtain the necessary experience for ministerial service?

- What are the best models of training for future ministers?

- How much freedom will they be allowed in order to lead in an imaginative but responsible way?

- What structures have to be put in place to enable ministers to stay long enough to effect strategic change?

- What can the churches learn from the way the ethnically diverse churches are led?

Ultimately leaders lead because of the vision they have for the future. How is that vision formed? How is it best communicated? These are not just academic questions; they are ones of vital importance if the Church that Jesus is building in the UK is to be ready to meet the storms that undoubtedly will come.