In 1700 fewer than two percent of the world’s population lived in urban places. Beijing and London were the only cities that had populations surpassing one million. By 1900 an estimated nine percent of the world’s population was urban. London was then the only “super-city” on the globe. In 1950 twenty-seven percent of the world’s population lived in cities and seventy-three percent of the world’s people lived on the land. By 1996 however, the world was growing by 86 million people a year and for the first time more than fifty percent of the world’s population lived in cities. While the rural percentage of the world’s population is declining, rural population is still growing in absolute numbers. The United Nations—which offers the most conservative growth estimate—projects that by 2025 over sixty percent of the world's estimated 8.3 billion people will live in urban areas.

According to the World Heritage Centre, by 2020 the urban population of Asia will be around 2.5 billion, having doubled in twenty-five years. By then more than half of the urban areas of the planet will be in Asia, and those urban areas alone will contain over one-third of the world’s population. The same organization predicts that the cities of Asia will be growing twice as fast as cities in the rest of the world.

For all the challenges of urban areas—traffic, pollution, noise, high cost of living, crowded and often substandard living conditions, economic disparity, stress, psychological overload, long hours of commuting and violence—cities provide people in the developing world the best hope of education and income. People continue to be drawn to the city through migration and immigration.

As a heart pumps blood back and forth throughout a body, cities pump people around, on both a short-term and long-term basis. This makes it harder to develop stable churches in cities, but it creates the opportunity for global evangelisation as people find themselves relocated from one city to another.

Surely, God has a purpose in this.

Whether through migration or immigration, the socially dislocating experience of moving into a city tends to loosen ties to local divinities and opens doors for the gospel.

Often, people who move to the city are not just moving away from something, but moving toward something as well. People move to the city wanting change, yearning for new things, expecting to be exposed to new ideas and desiring to make a new start. Whether through migration or immigration, the socially dislocating experience of moving into a city tends to “loosen ties to local divinities,” and opens doors for the gospel.

Given these facts and predictions, any discussion about the mission of the Church for the twenty-first century must include urban strategy. Furthermore, because of the strategic nature of cities as (1) centres of influence, business and finance and (2) hubs of communication and transportation, education, entertainment, power and influence, to reach the world for Christ we will have to not merely include urban ministry but prioritize it. In fact, we cannot evangelize the world unless we reach the vast, growing and influential urban centres of the world. ![]()

Developing strategies for reaching the world’s urban areas for Christ cannot be based on the same methodologies or approaches that may or may not have worked elsewhere in other times. If we continue doing what we have done, we will end up with no more success than we are currently experiencing. When we talk about urbanization, we are talking about a context that is crowded, diverse, dangerous and intense. To pursue mission with the world’s cities implies that we will have to re-discover, develop and make known theologies of urban mission that speak to people where they live and touch them where they hurt. Our strategies must be holistic and relevant. They must direct the gospel and transformational ministries toward the most urgent social and economic challenges.

This article is an attempt to formulate a biblical and urban hermeneutic that will help urban ministry practitioners to take the categories of “place” and “space” more seriously, however challenging this might be.1 Included is an emphasis upon the lived experience of practitioners because this is at the heart of all urban reflection and action. It is our desire to illustrate what this looks like for urban ministry practice.2 However, city/regions cannot be divorced from the philosophy of urbanism and globalization.

Pursuing the Transformation of City/Regions

Some people look at the spiritual and social plight of the city, ask, “Where is the Church?” and then rush to critique its lack of significant involvement in the complexities of the city. It might be better to ask “What will the Church look like?” in the midst of this plurality and the competing worldviews that a practitioner runs into on a weekly basis. There are two principal sources of information that inform contextual urban ministry and help to understand what the Church will look like: (1) our Christian traditions and (2) worldview and culture.

Christian Traditions: Listen and Learn

The first source of information that informs urban ministry comes from our Christian traditions: our study of the scriptures, Church history and Christian theology. However, pursuing the mission of God in our city/regions is always done in a specific social context. The practitioner and the congregation need to listen and learn from that context. (Padilla 1979; Schreiter 1986; Smith 1996).3

The process of interpreting the biblical text and the context (referred to as hermeneutics) becomes a true exchange between gospel and context. We come to the infallible message with an exegetical method to understand a biblical theology of place. We ask, “What does God say through scripture regarding this particular context?” This includes place, problems, values and worldviews. This initial dialogue sets us on a long process where the more we understand the context, the more we will experience fresh readings of the Bible. Scripture illuminates life and life also illuminates scripture! This dialogue must also include the practitioner’s worldview and that of the community in which he or she bases his or her initiatives.

Scripture illuminates life and life also illuminates scripture.

Studying the biblical text and the context in this fashion represents a holistic enterprise in which the Holy Spirit guides the interpreters to a more complete reading and understanding of scripture and a more complete understanding of the culture. There is an ongoing, mutual engagement of the essential components of the process. As they interact, they are mutually adjusted. In this way, we come to scripture with relevant questions and perspectives. This results in a more attentive ear to the implications of the exegetical process and an ensuing theology that is more biblical and pertinent to the culture. As we move from the cultural context through our own evolving worldview to the Bible and back to the context, we adopt an increasingly relevant local reflection and more appropriate initiatives.

As we listen to scripture and walk through our various situations in life, we are faced with the question “How can we hear and apply God's word in our cities and neighbourhoods?” ![]()

Urban Worldviews and Culture

Many people do cultural studies and wrestle with the sociology of place. On a different track, other practitioners try to get their heads around the philosophies that make up the personality of our cities (sometimes referred to as a horizon). The urban ministry practitioner should be able to put these two approaches together so that in examining the city as a place, he or she is also learning to look closely at the worldviews that are reflected in the urban context. Urban practitioners need to be able to identify local worldviews in order to understand the spirituality in their particular context. A worldview is primarily a lens through which we understand life. Generally speaking, it includes a series of presuppositions that a group of people holds, consciously and unconsciously, about the basic make-up of the community, relationship, practices and objects of daily life, whether they are of great signification or of little importance. They are like the foundations of a house—vital but invisible. The make-up of a worldview is based on the interaction of one’s ultimate beliefs and the global environment within which one lives. They deal with the perennial issues of life like religion and spirituality; yet contain answers to even simple questions such as whether we eat from individual plates or from a common bowl.

Worldviews are communicated through the channel of culture. We should be careful to not confuse culture and worldview, although they are in constant relationship with one another. Culture is foremost a network of meanings by which a particular social group is able to recognize itself through a common history and a way of life. This network of meanings is rooted in ideas (including beliefs, values, attitudes and rules of behaviour), rituals and material objects, including symbols that become a source for identity such as the language we speak, the food we eat, the clothes we wear and the way we organize space. This network is not a formal and hierarchical structure; it is defined in modern society by constant change, mobility, reflection and ongoing experiences.

This is in contrast to traditional societies where culture was transmitted directly from one generation to the next within the community structures. Modernity still transmits some aspects of culture like language and basic knowledge directly through the bias of the school system, but once this is done, the transmission of culture through friendship, peers and socio-professional status becomes more important. Our understanding of social context raises several foundational questions:

- How do we know a context when we see one?

- How big is a context?

- How long does it last?

- Who is in it and is out of it, and how do we know?

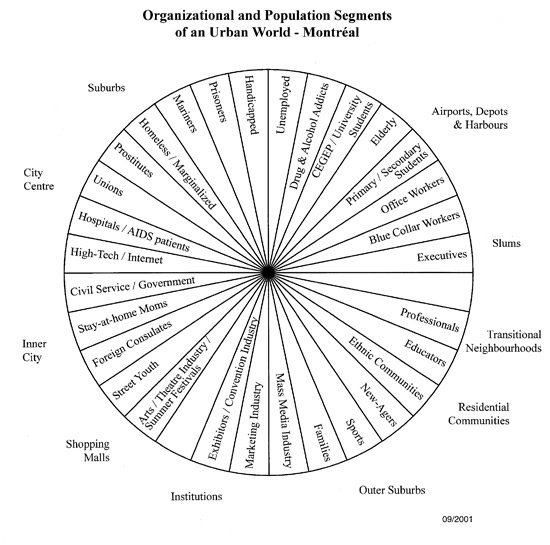

In reality, the complexity of the city means we constantly ask these questions. The following representation inspired by the work of urban ministry practitioners in Montreal, Canada, seeks to take into account most of the factors that determine context.

|

This hermeneutical approach to the missio Dei or mission of God in city/regions reaffirms “the scandal of particularity.” Urban mission is rooted in the very particular stories of the Bible and especially of the good news of Jesus’ incarnation and the cosmic goal God has undertaken to re-inaugurate his reign through his death on the cross (Hall 2003). This very notion has alienated a great number of modern theologians from the historic understanding of the Christian faith. There has been a tendency to question the uniqueness of God’s participation with creation through the history of Israel and in the person of Jesus Christ. Instead, the concept of mission was broadened almost to the point that the Church was stripped of any responsibility for proclamation and service; the Church was excluded from mission. This exclusion of the Church resulted in an argument that God was “working out his purposes in the midst of the world and its historical processes.” It was simply the Church’s responsibility to serve missio Dei by pointing to God “at work in world history and name him there.” ![]()

This focus on God’s action in the world and its historical processes, to the exclusion of the Church’s mission of witness and service, was closely tied to what could be described as an exaggerated eschatology in which the fullness of God’s kingdom, of God’s shalom, was expected to be accomplished through the social and political motions of history. In order to avoid the severing of the missio Dei concept from the teachings of classical Christianity, and in an attempt to hold together the whole mission of God for the whole city, it will be important to hold the universal concept of the missio Dei together with the particular history of God’s plenary revelation in the person and work of Jesus Christ and read the story in our own unique contexts.

Contextualisation and Transformation

Contextualisation literally means a “weaving together.” In this article it implies the interweaving of the scriptural teaching about the city and the Church with a particular, present-day context. The very word focuses the attention on the role of the context in the theological enterprise. In a very real sense, then, all doctrinal reflection from scripture is related in one way or another to the situation from which it is born, addressing the aspirations, the concerns, the priorities and the needs of the local group of Christians who are doing the reflection.

Contextualisation begins with an attempt to discern where God by his Spirit is at work in the context. It continues with a desire to demonstrate the gospel in word and deed and to establish groups of people who desire to follow Jesus in ways that make sense to people within their (cultural) context, presenting Christianity in such a way that it meets people’s deepest needs and penetrates their worldview, thus allowing them to follow Christ and remain within their culture.4

Contextualisation begins with an attempt to discern where God by his Spirit is at work in the context.

The task of contextualisation is the essence of urban reflection and action. The challenge is to remain faithful to the historic text of scripture while being mindful of today's realities. An interpretative bridge is built between the Bible and the situation from which the biblical narrative sprang, to the concerns and the circumstances of the local group of Christians who are doing the reflection.

- The first step of the hermeneutic involves establishing what the text meant at the time it was written; what it meant “then.”

- The second step involves creating the bridge to explore how the text is understood in meaningful terms for the interpreters today; what it could mean “now.”

- The final step is to determine the meaning and application for those who will receive the message in their particular circumstances, as present day interpreters become ambassadors of the good news (Hiebert 1987).

Contextualisation is not just for the one communicating, nor about the content that will be passed along. It is always concerned with what happens once we have communicated and about the ultimate impact of the message on the audience.

Holistic Transformation

But for what purpose does the urban ministry practitioner pursue contextualisation? Why listen to both the present context and Christian tradition, including our study of the scriptures, Church history and theology? Increasingly we hear the use of the word transformation as a term that encompasses all that the Church does as followers of Jesus in God’s mission in the city. But what does this mean? What does it entail?

The 1990 Population Fund Report on cities laid out interesting strategies for more livable urban areas. The Population Crisis Committee carried out the most complete study ever done. Data was gathered from the world’s largest one hundred metropolitan areas. Based on a thirteen-page questionnaire, the researchers wanted to determine the quality of life in these places. Ten parameters5 were chosen to determine the livability of these cities. Based on these criteria an urban living standard score was calculated. The parameters provide a glimpse of what transformation might include.

Beatley and Manning offer this picture: “To foster a sense of place, communities must nurture built environment and settlement patterns that are uplifting, inspirational and memorable, and that engender a special feeling and attachment…a sustainable community where every effort is made to create and preserve places, rituals and events that foster greater attachment to the social fabric of the community” (1997, 32). 6

Inspired by John de Gruchy reflections7, I would suggest that a transformed place is that kind of city that pursues fundamental changes, a stable future and the sustaining and enhancing of all of life rooted in a vision bigger than mere urban politics.

If we accept that scripture calls the people of God to take all dimensions of life seriously, then we can take the necessary steps to a more holistic notion of transformation. A framework that points to the best of a human future for our city/regions can then be rooted in the reign of God. ![]()

In Jewish writings and tradition is the principle of shalom. It represents harmony, complementarity and establishment of relationships at the interpersonal, ethnic and even global levels. Psalm 85:10 announces a surprising event: “Justice and peace will embrace.” However, a good number of our contemporaries see no problem with peace without justice. People looking for this type of peace muzzle the victims of injustice because they trouble the social order of the city. But the Bible shows that there cannot be peace without justice. We also have a tendency to describe peace as the absence of conflict. But shalom is so much more. In its fullness it evokes harmony, prosperity and welfare.

In the New Testament the reign of God is the royal redemptive plan of the creator, initially given as a task marked out for Israel, then re-inaugurated in the life and mission of Jesus. This reign is to destroy his enemies, to liberate humanity from the sin of Adam and to ultimately establish his authority in all spheres of the cosmos: our individual lives, the Church, society, the spirit world and the ecological order. Yet, we live in the presence of the future. The Church is “between the times,” as it were: between the inauguration and the consummation of the kingdom. It is the only message worth taking to the whole city!

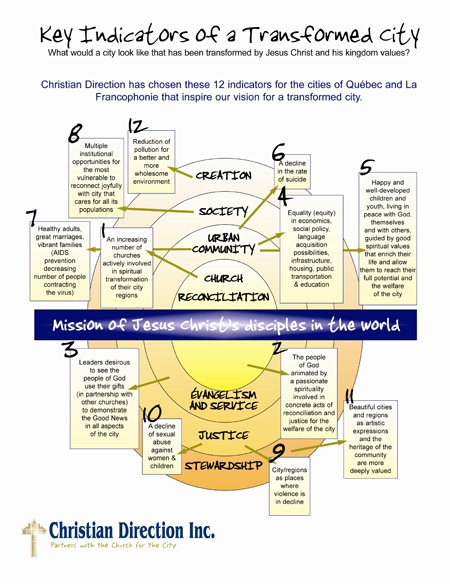

The Church—Participating in City Transformation

In light of all these realities an increasing number of congregations in my (Glenn Smith) city, Montréal, have adopted the following schema and the twelve indicators as a vision of what our transformed city would look like. Rooted in four concentric circles that represent God’s concern for all of life, beginning with the congregation that embodies shalom and reconciliation and subsequently demonstrates the good news in their community, society and in all of the created order. But so as to measure realistically the vision, we have articulated twelve indicators of the type of transformation we are pursuing. These address contextual concerns in our city. Accompanying these indicators are baselines based on research on the state of life in the city. Congregations work together to pursue the welfare of the city.

This vision seeks to help the Church participate in the transformation of the city, particularly in an era of human brokenness.

|

Endnotes

(1) One of the few texts on urban geography that takes these two distinct categories seriously is by A. M. Orum and X. Chen, The World of Cities: Places in Comparative and Historical Perspective (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003). For these authors, place is the specific locations in space that provide an anchor and meaning to who we are. (see pages 1, 15, 140 and 168) Our sense of place is rooted in individual identity, community, history and a sense of comfort (11-19). Space, on the other hand, is a medium independent of our existence in which objects, ideas and other human persons exist behaving according to the basic laws of nature and thought (see pages 15, 140 and 160-170).

(2) This approach to urban mission hermeneutics is intentional on the editor’s part. A lived experience in context is a preliminary step in all contextual theologies. This is certainly true in theologies of liberation. Leonardo Boff and Clodivis Boff call this the preliminary stage of all theologising, a living commitment with the poor and oppressed. Robert Schreiter summarizes the biblical foundation well, “…the development of local theologies depends as much on finding Christ already active in the culture as it does on bringing Christ to the culture. The great respect for culture has a Christological basis. It grows out of a belief that the risen Christ’s salvific activity in bringing about the kingdom of God is already going on before our arrival. From a missionary perspective there would be no conversion if the grace of God had not preceded the missionary and opened the hearts of those who heard.” (Constructing Local Theologies. Maryknoll, New York, USA: Orbis, 1986, 29).

(3) For a list of all references in this article, visit http://www.direction.ca/wb/pages/accueil/les-ministeres/urbanus.php.

(4) This reflection is inspired by an article by David Whiteman “Contextualization: The Theory, the Gap, the Challenge” International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 21:1, January 1997, 2-7.

(5) (1) Public safety based on local police estimates of homicides per 100,000 people; (2) Food costs representing the percentage of household income spent on food. (3) Living space being the number of housing units and the average persons per room. (4) Housing standards being the percentage of homes with access to water and electricity. (5) Communication is the number of reliable sources of telecommunications per 100 people. (6) Education is based on the percentage of children, aged 14-17 in secondary schools. (7) Public health criteria are based on infant deaths per 1,000 live births. (8) Peace and quiet based on a subjective scale for ambient noise. (9) Traffic flow being the average miles per hour during rush hour. (10) Clean air based on a one-hour concentration in ozone levels.

(6) The United Nations Millennium Development Goals provide a marvelous starting point for a reflection on transformation as well for a local congregation. The reader is invited to consult the webpage: www.un.org/millenniumgoals.

(7) John W. de Gruchy, Christianity, Art and Transformation: Theological Aesthetics in the struggle for Social Justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

(This article was written in collaboration with Rev. Klaus Keid of Germany, Rev. Robyn Pebbles of Australia, Dr. Delia Nuesch-Olver of the United States and Dr. David Koop of Canada.)